Samurai Spectacle

Japan’s Matsuri Ceremony

Text and photography by Eric Pasquier

Every May, Japanese CEOs, lawyers, businessmen and clerks, transform themselves into samurais, the secular warriors of imperial Japan.

A celebration of medieval feudalism, this annual ceremony – rooted in Japanese history – transports players and spectators back in time, and offers a spectacle worthy of a Hollywood production.

Grandiose, immobile, impassive… Standing next to his Toyota four-by-four, his eyes fixed on the horizon, the Japanese gentleman has arrived at the meeting place at dawn.

For the last several years, he hasn’t missed a single one of these annual celebrations. It has become a ritual for him, a ceremony that he has chosen to partake in with near-religious devotion.

And he has come magnificently apparelled: a shiny, black, wooden shield covers his chest and on his head is a helmet gleaming with gold-leaf. A true samurai, straight out of the 12th century.

Nearby, a fellow warrior is practising his moves. He slices the air with his sword, attacking an imaginary enemy.

The weight of his armour doesn’t seem to have the slightest effect on the swiftness or precision of his movements.

A two-hour drive from Tokyo, in the forest of Nikko, thousands of Japanese men gather for the ritual of the ‘Procession of One Thousand Warriors’. In this cedar forest, veiled in a gentle haze of early-morning mist, the Japanese Imperial Army of yesteryear is revived in Matsuri, one of the country’s most popular religious ceremonies.

One thousand men, one thousand samurais. In military order and with textbook Japanese discipline, two columns of warriors escort three sacred palanquins. From the temple of Tosho-gu to the ancient revered temple Futurasan, they parade, armed with sabres, spears and bows and arrow. A long, slow procession that is a modern perpetuation of the cult of Japan’s feudal past.

Dressed in their armour – which actually belongs to the State since it is at least three centuries old – the men truly step back into the past. Their faces remain impassive and time seems to stand still. The samurai of yesteryear, noble, virtuous and courageous, are revived, still standing by at the ready. For to be a samurai, is to be at the service of one’s lord and master. It is to obey utterly the laws of bushido, the code of honour wherein one must have a “soul of perfect transparency” and be willing to “let blood flow like the leaves of a cherry tree”.

Matsuri is a custom dating back to the dawn of Imperial Japan, updated and modernised for today’s working man. A custom of which the participants are fiercely proud. “It is a great honour,” says an old man in ceremonial dress, “to wear the armour of our ancestors.” A single helmet alone can cost $50,000 and certain ensembles are estimated to be worth up to $150,000 – although the value of what these items represent, and the pride they evoke, make them priceless.

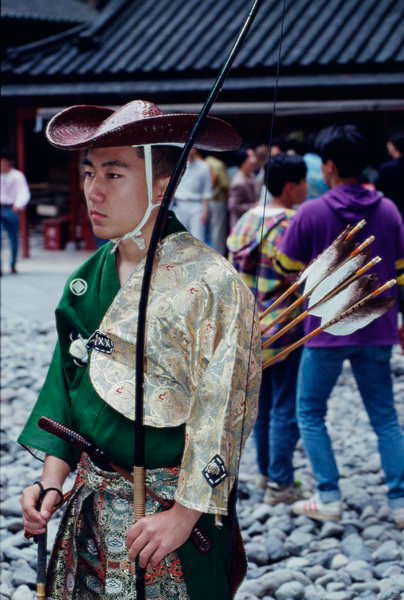

A bit further along, a young man is wearing leather ‘breeches’ over his elegant kimono. He is an archer and wears no armour. On his back, in an intricately-knotted system of ropes are four or five arrows; his long, bamboo bow is in his hand. The ceremony is certainly not limited to the parade itself.

With all the finery that the Japanese are so famous for, the young archer checks the perfect alignment of the feathers of his arrows.

The competition is taken very seriously; each contestant visibly puts his all into the presentation and performance of his art.

Meanwhile, an elaborately decorated horse waits, neighing impatiently. A multi-coloured silk garment covers its flanks. The young archer leaps upon his horse and digs his heels into its sides. The animal tears off, along the humid and slippery surface. The horseman lets go of the reins, reaches back and grabs an arrow, and expertly positions it into the groove of his bamboo bow. As the animal gallops along the rough surface, the archer pulls back the arrow with all his strength and aims its sharp point with one eye at his target. At the bottom of the hill the archer lets his arrow fly. Behind him, another mounted archer is already in hot pursuit.

The next stage of the competition is reserved for the regular archers. Although it looks more relaxed, since these men don’t have to sit on a rushing steed while they take aim, theirs is a time-honoured ritual of precision. The position of their bodies, their gestures and the firing of the arrow are all regulated. While lined up, they loosen their arrows at the common target at exactly the same moment. The harmony and timing of the group is the very image of Japanese conformity and precision.

As night approaches, the archery competition has finished. The would-be warriors carefully load their magnificent three-century-old armour back into the trunks of their Toyotas and Nissans.

In Minakotu, one of the more ‘in’ neighbourhoods of the Japanese capital, the director of Japan Sword Co. Ltd, Inami Tomihiko, exhibits a magnificent collection of masks and armour in his gallery. And naturally, every piece has a long, rich history behind it: “The cult of our ancestors developed with the prosperity of our country,” he says. “What do today’s millionaires fantasise about? About owning an authentic, full set of samurai armour!”

A few doors down from Tomihiko’s shop, the last remaining manufacturer of samurai armour is putting the finishing touches on a costume. Itchu Kato, whose father and grandfather held the same job, produces replicas of armour ensembles of the most famous samurais.

“This 12th century set of Murasaki armour you see here took me three years to create. It is worth twenty thousand dollars, but I’m not in this for the money,” he says. All around him are miniature replicas of katchus or sets of armour. They are everywhere; the result of a life devoted exclusively to a single passion. Certain pieces sell for up to three million but they still sell. Because in the Japan of today where the past and future collide with such incredible intensity, a select few parents still hold the fervent wish to make their sons live the customs of their forefathers. And so, to initiate their offspring to the ideal of the samurai – a reflection of Japan’s exceptional cultural heritage – these parents offer their children a complete set of traditional samurai armour lovingly manufactured in the atelier of Itchu Kato.